In the Philippines, when people talk of sea bass, they are referring to barramundi or locally known as ‘apahap’. Sea bass or Barramundi (Lates calcarifer), is a fresh-water species found in tropical and semitropical regions ranging from the Persian Gulf to China, and found as far south as Australia, as well as north to India. This species has an elongate body form with a large, slightly oblique mouth and an upper jaw extending behind the eye.

In the Philippines, when people talk of sea bass, they are referring to barramundi or locally known as ‘apahap’. Sea bass or Barramundi (Lates calcarifer), is a fresh-water species found in tropical and semitropical regions ranging from the Persian Gulf to China, and found as far south as Australia, as well as north to India. This species has an elongate body form with a large, slightly oblique mouth and an upper jaw extending behind the eye.

Barramundi is broadly referred to as Asian sea bass by the international scientific community, although it is also known as giant perch, giant seaperch, Australian seabass, and by a variety of names in other local languages, such as ikan siakap in Malay and pla krapong in Thai. Among Filipinos, it is called by several names: apahap, bulgan, kakap, salongsong, katuyot, and matang pusa.

Barramundi is one of the most popular fishes in Thai cuisine. It is often eaten steamed with lime and garlic, as well as deep-fried or stir-fried with lemon grass, among variety of many other ways. In the Philippines, it is highly prized in seafood restaurant because of its delectable taste and white meat.

Raising sea bass is a profitable venture. It can be grown in marine cages, brackish water ponds and even fresh water net pens with minimal adaptation.

PRODUCTION

Production Systems

Seed Supply

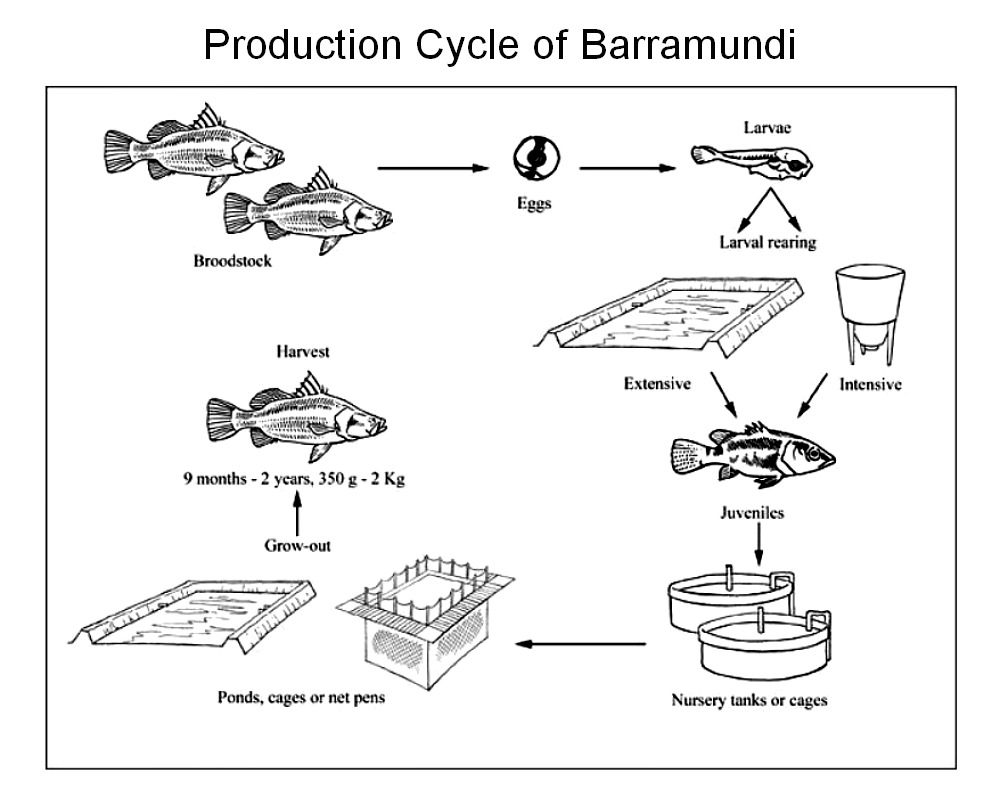

While barramundi fingerlings are still collected from the wild in some parts of Asia, most seed supply is through hatchery production. Hatchery production technology is now well established throughout the culture range of this species.

Rearing Fingerlings

Barramundi brood stock are held in floating cages or in concrete or fiberglass tanks. They may be maintained in either fresh or seawater but must be placed in seawater (28–35‰) prior to the breeding season to enable final gonadal maturation to take place. Barramundi show no obvious external signs of gonadal development and must be examined by cannulation to determine their gender and reproductive status, although milt can be expressed easily from male fish during the spawning season.

Barramundi brood stock are usually fed with ‘trash’ fish or commercially available baitfish. In order to improve the nutritional composition of the brood stock diet, and prevent diseases associated with vitamin deficiencies, a vitamin supplement may be injected into, or mixed with, the baitfish prior to feeding.

Asian barramundi have been induced to spawn by manipulation of environmental parameters (salinity and temperature) to simulate the migration to the lower estuary, and the tidal regime there at the time of natural spawning. The same techniques have proven unsuccessful with Australian populations of barramundi, which generally require hormonal induction to spawn. Barramundi have been successfully spawned using a range of hormones at various doses, which were administered by techniques including injection, slow-release cholesterol pellets and osmotic pumps. Induced spawning of barramundi is now generally carried out using the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogues (LHRHa) (Des-Gly10)D-Ala6, Pro9-LH-RH ethylamine and (Des-Gly10)D-Trp6, Pro9-LH-RH ethylamine.

Pre-spawning behavior involves the male fish pairing with a female and rubbing its dorsal surface against the area of the female’s genital papilla, erecting its fins and ‘shivering’. In the absence of such displays, egg release may occur but they are not fertilized. Spawning occurs 34–38 hours after injection, usually around dusk, and may be accompanied by violent splashing at the water surface. Barramundi will often spawn for up to five consecutive nights.

At spawning, the sperm and eggs are released into the water column and fertilization occurs externally. Barramundi eggs are 0.74–0.80 mm in diameter with a single oil droplet of 0.23–0.26 mm diameter. The eggs are collected from spawning tanks using fine mesh (around 300 µm) egg collection nets through which tank water is diverted. If barramundi are spawned in cages, the cages are lined with a fine mesh ‘hapa’ net that retains the eggs inside the cage, enabling their later removal to the hatchery.

Fertilized eggs undergo rapid development and hatching occurs 12–17 hours after fertilization at 27–30 °C. Newly hatched larvae have a large yolk that is absorbed rapidly over the first 24 hours after hatching, and is largely exhausted by 50 hours after hatching. The oil globule is absorbed more slowly and persists for about 140 hours after hatching. The mouth and gut develop the day after hatching (day two) and larvae commence feeding from 45–50 hours after hatching.

Hatchery Production

Barramundi are generally reared using ‘green water’ intensive techniques, in circular or rectangular concrete tanks or in circular canvas tanks up to 26 m³ capacity. A microalgal culture (usually Tetraselmis spp. or Nannochloropsis oculata) is added to the rearing tanks at densities ranging from 8–10×10³ to 1–3×105 cells/ml. Intensively reared barramundi are fed on rotifers (Brachionus plicatilis) from day two (where day one is the day of hatching) until day 12 (or as late as day 15), and on brine shrimp (Artemia sp.) from day eight onwards. Both rotifers and brine shrimp fed to barramundi are cultured on microalgae or commercial enrichment products to increase levels of highly unsaturated fatty acids. The freshwater cladocerans Daphnia and Moina have been used to supplement, or replace, brine shrimp as prey for intensively reared barramundi larvae. Overall survival for intensively-reared barramundi larvae from hatching to about 10 mm TL generally ranges from 15–50 percent. More recently, compounded micro diets have been used to partly or totally replace brine shrimp in the intensive larval rearing of barramundi.

Barramundi fingerlings are also produced using extensive (pond-based) rearing procedures. Pond areas used for the extensive larval rearing of barramundi range from 0.05 to 1 ha and may be earthen or plastic lined. They are relatively shallow (<2 m) to promote maximum production of phytoplankton and to prevent stratification. Larval rearing ponds are managed through the application of inorganic and organic fertilizers to produce a ‘bloom’ of suitable zooplankton concomitant with the introduction of the newly hatched barramundi larvae. Barramundi larvae are stocked at densities of 400 000–900 000/ha. Continued pond management focuses on supporting adequate zooplankton populations for the developing larvae, and ensuring that water quality criteria are maintained. Barramundi are harvested from the ponds when they reach 25 mm TL or greater (about three weeks after stocking), and are then transferred to nursery tanks. Survival of extensively reared barramundi averages about 20 percent, but is highly variable, ranging from zero to 90 percent. Production rates of up to 640 000 fish/ha have been achieved in extensive rearing.

Nursery

Barramundi juveniles (1.0–2.5 cm TL) may be stocked in floating or fixed nursery cages in rivers, coastal areas or ponds, or directly into freshwater or brackish water nursery ponds or tanks. The fish are fed on minced trash fish (4–6 mm) or on small pellets. Vitamin premix may be added to the minced fish at a rate of 2 percent. This nursery phase lasts for 30 to 45 days; once the fingerlings have reached 5–10 cm TL they can be transferred to grow-out ponds.

Cannibalism can be a major cause of mortalities during the nursery phase and during early grow-out because barramundi will cannibalize fish of up to 61–67 percent of their own length. Cannibalism may start during the later stages of larval rearing and is most pronounced in fish less than about 150 mm TL; in larger fish, it is responsible for relatively few losses. Cannibalism is reduced by grading the fish at regular intervals (usually at least every seven–ten days) to ensure that the fish in each cage are similar in size.

On-growing Techniques

Most barramundi culture is undertaken in net cages. Both floating and fixed cages are used; these range in size from 3×3 m up to 10×10 m, and 2–3 m depth. In Australia and the United States of America, a number of barramundi farms have been established using recirculation freshwater or brackish water systems with a combination of physical and biological filtration. These farms may be located in regions where barramundi could not otherwise be farmed because of consistently low temperatures (southern Australia, north-eastern United States of America). The major advantage of such culture systems is that they can be sited near to markets in these areas, thus reducing transport costs for the finished product.

The stocking densities used for cage culture generally range from 15 to 40 kg/m³, although densities may be as high as 60 kg/m³. Generally, increased density results in decreased growth rates, but this effect is relatively minor at densities under about 25 kg/m³. Barramundi farmed in recirculation production systems are stocked at a density of about 15 kg/m³.

Barramundi are also farmed in earthen or lined ponds without cages; a technique known in Australia as ‘free ranging’. Juvenile barramundi (20–100 g) are cultured in brackish water ponds at 0.25–2.0 fish/m². In Asia, barramundi may be polyculture in brackish water ponds with tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) as a food source.

Feed Supply

Most barramundi are now fed on compounded pellets, although ‘trash’ fish is still used in areas where it is cheaper or more available than pelleted diets. Barramundi fed ‘trash’ fish are fed twice daily at 8–10 percent body weight for fish up to 100 g, decreasing to 3–5 percent body weight for fish over 600 g. Vitamin premix may be added to the trash fish at a rate of 2 percent, or rice bran or broken rice may be added to increase the bulk of the feed at minimal cost. Food conversion ratios (FCRs) for barramundi fed on trash fish are high, generally ranging from 4:1 to 8:1.

Barramundi fed pellets are generally fed twice each day in the warmer months and once each day during winter. Larger farms may use automatic feeder systems, though smaller farms hand-feed. Barramundi have achieved FCRs of 1.0–1.2:1 under experimental conditions, but in commercial farm conditions FCRs of 1.6–1.8:1 are usual. FCR varies seasonally, often increasing to over 2.0:1 during winter.

Harvesting Techniques

For barramundi farmed in cages, harvesting is relatively straightforward, with the fish being concentrated into part of the cage (usually by lifting the net material) and removed using a dip net. Harvesting barramundi ‘free-ranging’ in ponds is more difficult, and requires seine-netting the pond or drain harvesting.

Handling and Processing

After harvesting, the barramundi are placed in an ice slurry to kill them humanely and preserve flesh quality. In Australia, most farms do not process the fish, but sell them ‘gut in’. Some larger Australian farms have processing facilities to process fillet product from larger (2–3 kg) fish. Fresh barramundi is generally transported packed in plastic bags inside Styrofoam containers with ice. There is a limited market for live barramundi in Australia and in Southeast Asia. Fish are usually transported live in tanks by truck.

For more information, contact:

Finfish Hatcheries Inc. (FHI)

Maribulan, Alabel, Sarangani, Philippines

Phone: (083) 508-2300

Fax: 508-2305

Finfish Hatchery, Inc.

Makati City, Metro Manila, Philippines

Phone: (632) 893-7105, 815-2142

Email: [email protected]

Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources

Regional Office No. 6

M. H. del Pilar St., Molo, Iloilo City

Tel: (033) 336-6748

Fax: (033) 336-9432

Email: [email protected]

Source: agribusinessweek.com, trc.dost.gov.ph, www.fao.org; Photo: helifish.com.au, agribusinessweek.com